Couple dominance, dark personality traits, and power motivation

Javier I. Borráz-León(1), Coltan Scrivner(1,4), Oliver C. Schultheiss(2), Royce Lee(3), Dario Maestripieri(1,4)

(a) Institute for Mind and Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

(b) Institute of Psychology, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany

(c) Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

(d) Department of Comparative Human Development, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Correspondence: Dario Maestripieri, dario@uchicago.edu

Abstract

In romantic couples, there is usually an asymmetry in decisional power such that one partner is dominant and the other is subordinate. This study investigated the role of sex, ethnicity, self-assessed social status, personality traits, and power motivation (both explicit and implicit) as potential determinants or correlates of couple dominance in a mixed-sex sample of 50 college students. Through a previously validated questionnaire, participants indicated whether they were dominant or subordinate in their romantic relationship, or whether the latter was egalitarian. Major personality domains, narcissism, psychopathy, borderline, autistic-like traits, and explicit power were assessed through questionnaires. Participants also underwent a Picture Story Exercise to evaluate their implicit motives. Being dominant and having high explicit, but not implicit, power motivation were associated with some psychopathic, narcissistic, and/or borderline traits, while autistic-like traits were associated with being subordinate. Traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and honesty-humility had weak associations with couple dominance and/or explicit or implicit power motivation. Our findings have implications for the understanding of dominance dynamics within couples and the relationship between personality traits and power motivation.

Introduction

Dyadic dominance constitutes the building block for status hierarchies and both are ubiquitous in socially living vertebrates, including many species of nonhuman primates as well as humans[1]. In human romantic couples, and especially in those in which the relationship has lasted more than a few weeks or months, there is usually an asymmetry in decisional power such that one partner is dominant and the other is subordinate[2][3][4][5][6]. In heterosexual couples, and especially in older couples or couples in which the man is much older than the woman, men are more likely to be dominant and women are more likely to be subordinate[5][7][8]. When decisional power is roughly shared within a couple and there is no clear-cut dominance, the relationship is considered to be egalitarian[5][7].

Clear asymmetries in characteristics other than age (e.g., cultural beliefs associated with ethnicity, explicit or implicit power motivation, attractiveness, status in society, earning power, personality traits, etc.), may or may not be associated with couple dominance. Explicit motivation refers to conscious interest in attaining a particular goal (e.g., power), whereas implicit motivation refers to unconscious dispositions[9][10].

In this study, we investigated the role of sex, ethnicity, self-assessed social status, personality traits, and power motivation (both explicit and implicit) as potential determinants or correlates of couple dominance. We are careful here to clarify that our use of the term ‘traits’ is specific to the instruments and the constructs that they measure, with no assumption that they are static over the life course, inherently genetically transmitted, or inherently pathological. We also will try to sidestep the debate over the precise boundaries between personality traits and personality disorders, given that our real interest here is understanding how personality constructs are related to dyadic relationships.

Previous research on personality traits assessed with the Big-Five Inventory has suggested that extraversion and introversion may be associated with dominance and subordination, respectively[11]. Assessments of personality with the HEXACO or the Autistic Quotient (AQ) questionnaire have suggested that honesty-humility and autistic-like traits may be associated with subordination in dyadic relationships as well[12][13]. In contrast, dominance may be predicted by narcissistic, psychopathic, and borderline personality traits, all of which seem to be characterized by some degree of self-assertiveness, aggressiveness, and attempts to control, manipulate, and exploit others[14][15][16][17]. Psychopathy, in particular, seems to be characterized, at least in high-functioning, socially successful individuals, by ‘fearless dominance’, that is the tendency to threaten, intimidate, control, and coerce others without any fear of the consequences of such behavior[18][19][20]. The hypothesis, however, that personality styles or traits associated with interpersonal aggression (narcissistic, psychopathic, or borderline), in both their dimensional and their pathological manifestations, may be characterized by high power motivation and the tendency to achieve dominance in dyadic relationships has not been systematically investigated[21].

In this study, we tested two non-mutually exclusive hypotheses: H1) that some personality traits (e.g., extraversion/introversion, honesty-humility, autistic-like traits, narcissism, psychopathy, and borderline) and explicit/implicit power motivation can independently predict or be associated with dominance or subordination in young romantic couples; H2) that explicit/implicit power motives are psychological mechanisms mediating the association between personality traits and couple dominance.

Whether H1) or H2), or both, are supported, we expect that greater power motivation (both explicit and implicit) is positively associated with narcissism, psychopathy, and borderline personality traits, and negatively associated with autistic-like personality and honesty-humility[13][15][22][23]. We further hypothesize that some of these associations may be moderated by sex (H3), such that the association between, for example, narcissism and power motivation, and between psychopathy and power motivation, would be stronger for men than for women, while the association between borderline personality traits and power motivation would be stronger for women than for men. The rationale for this hypothesis is that traits associated with interpersonal aggression can be interpreted as strategies to achieve social success, and that men and women, on average, may use different strategies to pursue and maintain power (i.e., dominance)[21][24][25] in heterosexual relationships, especially long-lasting ones.

Methods

Participants and study procedure

A sample of 50 subjects with an age range of 18-53 years participated in this study (nmales = 18, age: M = 27.38, SD = 8.89; nfemales = 32, age: M = 22.71, SD = 3.40); the difference in age between males and females was statistically significant (t = 2.141, p = 0.045). Participants were recruited on the University of Chicago campus through fliers, Marketplace, and a human subject recruitment website (Sona System). Study participants were all heterosexual and were not recruited from a clinical sample. Approximately 32% of the participants reported being Asian, 18% Black, 18% Hispanic/Latino, 28% White, and 2% Other. All study participants signed a written informed consent letter in which the procedure and objectives were clearly explained to them. The study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Social Science Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Study participants were asked to remotely complete the questionnaires listed below before they came in person to the lab in the Institute for Mind and Biology to undergo some experimental procedures not reported in this article. Since some components of the project required in person testing, data collection, which had begun in the Summer of 2019 had to be interrupted in January 2020, in conjunction with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S. and new research guidelines issued by the University of Chicago, which prohibited in person laboratory testing of human subjects.

Couple dominance

The Couple Dominance Assessment questionnaire (CDA; [5][7]) was used to assess dominance in a romantic relationship. Dominance was operationalized as having more decisional power[5][7]. From this perspective, one individual is dominant and the other is subordinate. If decisional power is perceived to be roughly equal within the couple, the relationship is described as egalitarian (this is more commonly the case for relationships at an early stage, in which two individuals just started dating, or for relationships that did not last more than a few months)[5][7]. A previous study in which two partners in each couple were separately interviewed showed a high degree of concordance in assessing who is dominant and who is subordinate, or whether the relationship is egalitarian[7]. This study also showed that couple dominance is generally consistent across many different domains of the relationship[7].

The CDA consists of a single question: in your romantic relationship, who is dominant and who is subordinate? Participants can answer the question with a score from 1 to 5, where 1 = I am definitely dominant over my partner; 2= I am somewhat dominant over my partner; 3= neither I nor my partner is dominant; 4= my partner is somewhat dominant over me; 5 = my partner is definitely dominant over me. If a participant is single at the time of the study, he or she is told to answer the CDA with reference to their most recent romantic relationship. The lower the score the higher the dominance.

Subjective social status

The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status was used to assess self-perceptions of social status in relation to a group of reference[26]. It presents a drawing of a ladder, a “social ladder”, and asks individuals to place an “X” on the rung on which they feel they stand. In this study, participants were asked to estimate their social status within their community of close acquaintances and friends.

Explicit power motivation

An early version of the Feeling Powerful and Desiring Power Scales (FPDPS; [27]) was used to evaluate participants’ explicit motivation and propensity for power. This scale contains 20 items (e.g., I always try to spot the dominant people in any situation) grouped into three subscales: feeling powerful, desire for power, and attention to power (see [27] for further details). Power scores are obtained through a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = disagree strongly to 5 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.86.

Implicit motives

A Picture Story Exercise (PSE) was administered to assess participants’ implicit motivational needs (n) for power, achievement, and affiliation (i.e., nPower, nAchievement, and nAffiliation) as well as activity inhibition, a frequent moderator of these motives and a predictor of leadership success[28][29]. Participants were instructed to write imaginative stories in response to the following four picture cues: Nightclub Scene, Boxer, Trapeze Artists, and Ship Captain. These pictures were selected because two of them suggested heterosexual relationship themes and all were suitable for eliciting power imagery, but also to a lesser extent imagery related to achievement and affiliation[30]. The third author (OCS), who was blind to the specific hypotheses tested in the present research and who had no knowledge of any of the other data collected from participants (including information related to participants’ sex), coded all PSE stories based on Winter’s[31] running-text system. According to the manual, power imagery is coded for themes related to strong forceful action; control and regulation of others; convincing or persuading others; providing unsolicited help or advice; concern with fame and prestige (or a lack thereof); and eliciting strong emotional reactions in others. Achievement imagery is coded for goals or performances that are positively evaluated; competing with others or winning; negative affect in response to failure; and unique accomplishments. Affiliation imagery is coded for positive interpersonal affect; sadness about disruption or loess of relationships; affiliative activities; and nurturant helping. The coder had achieved > 85% agreement with expert-coded materials contained in the manual, routinely teaches courses on coding motive imagery, and has extensive coding experience, with more than 10,000 stories coded. Word count and activity inhibition was determined by word count and search functions of the text processing software. For each participant, motive and activity inhibition (AI) scores were summed across picture stories to yield total nPower, nAchievement, and nAffiliation scores.

Following the recommendations by Schönbrodt et al.[32], motive and AI scores were partialled for total word count and the residuals, after conversion to z scores, used in all inferential statistical analyses. Two participants were excluded due to their word count being less than 120 words. Thus, all statistical analyses including implicit motives were run on a sample of 48 participants. Raw scores of each measure were as follows: nPower M = 19.63, SD = 11.92; nAchievement: M = 10.06, SD = 6.79; nAffiliation: M = 9.56, SD = 5.70; activity inhibition: M = 3.75, SD =3.35; word count: M = 466.98, SD = 152.56.

Major personality domains

The HEXACO Personality Inventory-Revised (HEXACO-PI-R;[33]) was used to assess the six major domains of human personality [(i.e., Honesty-Humility (α = 0.74), Emotionality (α = 0.79), Extraversion (α = 0.70), Agreeableness (α = 0.71), Conscientiousness (α = 0.77), and Openness to experience(α = 0.72)] through 60 items (e.g., I wouldn't use flattery to get a raise or promotion at work, even if I thought it would succeed). The scores were obtained using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Autistic-like personality traits

Autistic-like personality traits were assessed using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ; [34][34]) which contains 50 items (e.g., I like to plan activities I participate in carefully) rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.50.

Borderline traits

Borderline personality traits were assessed using the Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Features Scale (PAI-BOR; [35]). This scale contains 24 items (e.g., “my moods get quite intense”) grouped into four subscales [(i.e., affective instability (α = 0.77), identity problems (α = 0.75), negative relationships (α = 0.68), and self-harm (α = 0.74)], and rated on a 4-point Likert-scale ranging from 0 = false / not at all true to 3 = very true. Cronbach’s α for the general borderline score was 0.90.

Psychopathic traits

Psychopathic traits were assessed using the revised version of the Psychopathic Personality Questionnaire (PPI-R; [36]). This scale consists of 144 items [i.e., Machiavellian egocentricity (α = 0.72), fearlessness (α = 0.81), rebellious nonconformity (α = 0.79), blame externalization (α = 0.86), stress immunity (α = 0.75), cold heartedness (α = 0.80), social influence (α = 0.77), and carefree nonplanfulness (α = 0.73)], and rated on a 4-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 = false to 4 = true. Cronbach’s α for the general psychopathic score was 0.82.

Narcissistic traits

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI; [37]) was used to assess grandiose narcissism using 40 paired statements (e.g., I would do almost anything on a dare or, I tend to be a fairly cautious person) where participants have to choose which one of the options is closest to their feelings. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.80.

The Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; [38]) was used to assess vulnerable narcissism through 10 items (e.g., my feelings are easily hurt by ridicule or the slighting remarks of others). The scores were obtained using a 5-point Likert (1 = very uncharacteristic or untrue, strongly disagree, 5 = very characteristic or true, strongly agree). Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.74.

Statistical analyses

Data that did not meet the normality criteria was log-transformed to improve normality. Partial correlations, controlling for the confounding effects of age and sex, were used to study associations between couple dominance, power motivation (both explicit and implicit), and personality traits. Mediation analyses using explicit power motivation (the global score) as mediator were performed. In bootstrap analyses (10,000 bootstrap samples), mediation was considered statistically significant if the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effect did not include zero. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and its complement PROCESS version 4.1[39]. The package ‘corrplot’ version 0.92[40] from R version 4.2.2[41] was used to create Figure 1 in this study. All tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Couple dominance

Eleven participants reported being definitely dominant over their partners, nine reported being somewhat dominant over their partners, twenty-two reported an egalitarian couple relationship, five reported their partners being somewhat dominant over them, one reported his/her partner being definitely dominant over him/her. Two participants did not report information about couple dominance.

Sex, ethnicity, and psychological variables

Sex differences in psychological variables are presented in Table 1. In brief, men scored lower than women in the implicit motive “nAchievement” and in the HEXACO trait “agreeableness”, but higher in “honesty-humility”. Men also scored lower than women in the borderline traits “identity problems”, “negative relationships”, and in the global borderline score; they scored higher than women in the psychopathic trait “stress immunity”. Tendencies for men to score lower than women in the borderline trait “self-harm”, and higher than women in the psychopathic trait “carefree nonplanfulness” were also found. No significant sex differences were found for the other personality measures.

There were no significant differences in relation to ethnicity for any of the dependent variables of interest in this study (F(4,44) < 1.700, p > 0.150 in all cases).

Correlates and predictors of couple dominance

Couple dominance did not differ significantly in relation to participants’ sex (t = -0.613, p = 0.544) or ethnicity (F(4,42) = 0.141, p = 0.966). Couple dominance was not significantly associated with self-assessed social status (r = -0.146, p = 0.333) and tended to be negatively correlated to extraversion (r = -0.270, p = 0.069) and positively correlated to conscientiousness (r = 0.269, p = 0.071). Couple dominance was positively correlated to autistic-like traits (r = 0.311, p = 0.035) and negatively associated with grandiose narcissism (r = -0.382, p = 0.009) and with the psychopathic trait “Machiavellian egocentricity” (r = -0.291, p = 0.050). A tendency for a negative correlation between couple dominance and the psychopathic trait “fearlessness” (r = -0.275, p = 0.075), and for a positive correlation between couple dominance and the psychopathic trait “cold heartedness” (r = 0.279, p = 0.061) was also observed. No significant associations were found between couple dominance and the other psychopathy measures (r < 0.16, p > 0.20 in all cases), vulnerable narcissism (r = -0.041, p = 0.788), or any borderline trait (r < 0.04, p > 0.80 in all cases).

Couple dominance was negatively correlated with desire for power, attention to power, and the global power score (Figure 1), suggesting that dominant individuals have higher explicit power motivation than subordinate individuals (but there was no significant correlation between couple dominance and feeling powerful). A positive correlation between couple dominance and activity inhibition was also found (r = 0.346, p = 0.021). No significant associations were found for couple dominance and any measures of implicit motives (r < 0.19, p > 0.21 in all cases).

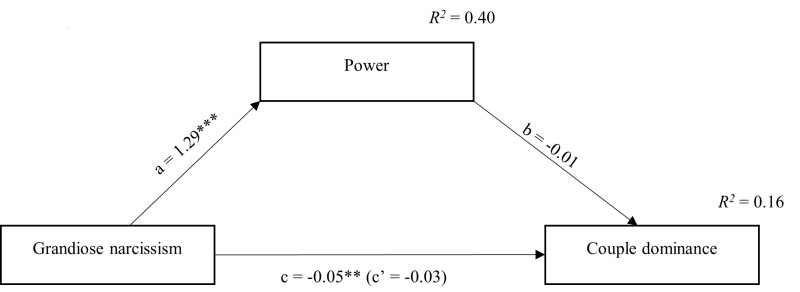

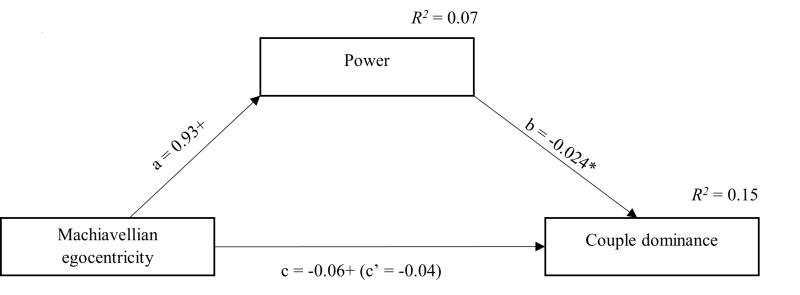

Based on the results of the correlational analyses, we tested with mediation models whether explicit power motivation, as measured by the global power score, was the mechanism mediating the association of grandiose narcissism and the psychopathy measure of “Machiavellian egocentricity ” and couple dominance, since regression analyses showed that grandiose narcissism and “Machiavellian egocentricity” predicted explicit power motivation (B = 1.319, β = 0.644, t = 5.837, p < 0.001 and B = 0.964, β = 0.278, t = 2.004, p = 0.051, respectively), and that explicit power motivation predicted couple dominance (B = -0.006, β = -0.356, t = -2.583, p = 0.013).

For the first model, we found that power does not significantly mediate the association between grandiose narcissism and couple dominance (Figure 2). For the second model, we found that power fully mediates the association between Machiavellian egocentricity and couple dominance (Figure 3).

Correlates of explicit power motivation

Positive correlations were found between the measures of explicit power motivation, except between “feeling powerful and “desire for power” (see Figure 1). No significant correlations between any measure of explicit power motivation and implicit motives were found (r < 0.115, p > 0.300 in all cases).

As shown in Table 2, “feeling powerful”, “attention to power”, and the global power score were positively correlated with extraversion, whereas “desire for power” and the global power score were negatively associated with honesty-humility. Grandiose narcissism was positively associated with “desire for power”, “attention to power”, and the global power score, whereas vulnerable narcissism was negatively associated with “feeling powerful”. A tendency for a positive association between vulnerable narcissism and desire for power” was also observed.

“Feeling powerful” was positively associated with the psychopathic trait “social influence”, whereas “desire for power” was positively correlated with “Machiavellian egocentricity”, “rebellious nonconformity”, “blame externalization”, “social influence”, and the global psychopathic score. “Attention to power” was positively associated with “social influence” and tended to be associated with “fearlessness” and “rebellious nonconformity”. Positive correlations between the global power score and “Machiavellian egocentricity”, “fearlessness”, “rebellious nonconformity”, “social influence”, and the global psychopathic score were also observed.

“Feeling powerful” was negatively correlated with the borderline trait “self-harm”. Tendencies for a negative correlation between “feeling powerful” and the global borderline score, and a positive association between “desire for power” and “affective instability” were also observed. No significant correlations were found for any power trait and autistic traits. Correlation coefficients and p values for each measure of power motivation are shown in Table 2.

Correlates of implicit motives

As shown in Table 2, the implicit power motive was positively associated with agreeableness. The implicit achievement motive was positively associated with the psychopathic traits “stress immunity” and “cold heartedness”, and with agreeableness, but negatively associated with the borderline traits “affective instability”, “identity problems”, and the global borderline score, as well as emotionality. The implicit affiliation motive was negatively correlated with vulnerable narcissism, the borderline traits “affective instability”, “identity problems”, and the global borderline score. Activity inhibition was positively associated with autistic-like traits. No significant results were found for the other personality traits.

Discussion

The present study explored associations between couple dominance, explicit and implicit power motivation, and personality traits in young men and women. Unlike a previous study in which couple dominance was assessed by interviewing both members of a romantic couple separately [7], in this study we administered the couple dominance questionnaire to individuals, not couples. However, the previous study showed high agreement between members of pairs in identifying who is dominant and who is subordinate in the couple [7]. Therefore, we are confident that the way couple dominance was assessed in this study provided valid and reliable information.

Compared to previous studies, in this study a relatively high number of individuals reported being in egalitarian relationships, without clear dominance, and more individuals reported being dominant than being subordinate (this occurred in spite of the fact that female participants were overrepresented in the sample relative to male participants). Although we do not have an immediate explanation for this pattern of results, it is possible that the young age of the study participants who were mainly in short-term relationships may have contributed to the findings.

One major novelty of our study is that we investigated couple dominance in relation to HEXACO-measured personality traits, autistic-like traits, and personality traits related to interpersonal aggression such as narcissistic, psychopathic, and borderline traits (see [42] for a previous study on narcissism and power in a college student population). Another major novelty is that we assessed power motivation with measures of both explicit (attention to power, interest in power, desire for power, as well as a global power score) and implicit motives (using the Picture Story Exercise; see [30]). Finally, we quantified self-assessed social status with the McArthur Social Status Scale (see Methods).

Consistent with one of our hypotheses, our results showed that individuals who are dominant in a romantic relationship, both men and women, score higher in explicit power motivation measures such as attention to power and desire for power than individuals who are subordinate (see also [3][6][43]). Moreover, dominant individuals tend to have personality profiles characterized by extraversion and interpersonally aggressive traits such as grandiose narcissism and psychopathy, whereas subordinate individuals are more likely to have autistic-like traits and to be higher in conscientiousness. Couple dominance was not significantly associated with implicit motives or with self-reported social status.

We further investigated the association between couple dominance, interpersonally aggressive personality traits, and power motivation with mediation analyses. These analyses showed that the global power score mediated the association between “Machiavellian egocentricity” and couple dominance, indicating that individuals high in “Machiavellian egocentricity”, both men and women, are more dominant in a romantic relationship and that this association is partially explained by their high explicit power motivation. The global power score did not mediate the association between grandiose narcissism and couple dominance.

Above and beyond our findings concerning couple dominance, our study also shed some light on interindividual variation in explicit power motivation. Explicit power motivation was somewhat associated with HEXACO personality traits (positively correlated with extraversion and negatively with honesty-humility; see also [13][44], but more so with interpersonal aggressive traits[45]. Consistent with our hypothesis, explicit power motivation was positively associated with narcissism (more strongly with grandiose than with vulnerable narcissism; see also [16][42] and with a number of psychopathy measures (“social influence”, “Machiavellian egocentricity”, “rebellious nonconformity”, “blame externalization”, “fearlessness”) as well as with the global psychopathic score. These results are consistent with previous research indicating that, both in high-functioning and in dysfunctional individuals, narcissism and psychopathy are characterized by social ambition, assertiveness, impulsive aggressiveness, and fearless dominance[15][16][17][18][20][21][22][46]. In our study, ‘desire for power’ was also positively associated with the borderline trait “affective instability”, whereas “feeling powerful” was negatively correlated with the borderline trait “self-harm” and the global borderline score[14][47][48].

We did not find any significant correlations between interpersonally aggressive traits and implicit power motives. Although one previous study reported significant associations between these traits and measures of implicit motives[21], we used different questionnaires to assess these traits as well as different measures of implicit motives (i.e., the PSE method instead of questionnaires). The small sample size of the present study might also account for our negative results concerning implicit power motives. However, previous research has shown that measures of explicit and implicit power motivation are not significantly correlated and tend to be associated with different behavioral outcomes[9][49]. Similarly, we found no significant correlations between our measures of explicit power motivation and the PSE-related implicit power motive measures.

Our findings concerning personality and explicit power motivation are consistent with the view that interpersonally aggressive personality traits such as narcissism, psychopathy, and borderline may be interpreted, at least in their milder and less pathological expressions, as functional social strategies employed to assert oneself and to control, coerce, manipulate, and exploit others[17][47][48][50] These traits, almost by definition, are mainly or almost exclusively expressed in inter-personal relationships. Although they may be characterized by emotion dysregulation, cognitive distortions, low empathy, and attachment insecurity, they all seem to share a strong interest in power and high motivation to obtain it. This can be true in the context of dyadic relationships, such as in romantic couples, but also in society at large. The specific mechanisms by which individuals who score high in narcissism, psychopathy, and borderline attempt to gain power over others may be substantively different and specific to each condition. It is possible that these strategies were initially deployed to defend against interpersonal threats, given their associations with exposure to childhood trauma[17].

Given that men and women may sometimes use different strategies to pursue and maintain power (for example, in heterosexual relationships), we hypothesized that the anticipated associations between power motivation and narcissism, psychopathy or borderline traits would be moderated by sex. This hypothesis was not supported by our data. Although we did find sex differences in some HEXACO personality traits (agreeableness and honesty-humility) and in some psychopathy (“stress immunity”, “carefree nonplanfulness”) and borderline (“identity problems”, “negative relationships”, “self-harm”; global borderline score) measures, there were no main effects of sex on any measures of explicit or implicit (nPower) power motives and no interactions between sex, personality, power motivation, and couple dominance. This may mean that when it comes to interpersonal power, men and women are more similar than they are different, or that in order to capture the effects of sex on these measures of motivation, studies with a sample size much larger than ours are needed.

As for the implicit motives other than power, we found that nAchievement was positively associated with the psychopathic traits “stress immunity” and “cold heartedness”, and with agreeableness, but negatively associated with the borderline traits “affective instability”, “identity problems”, and the global borderline score. nAffiliation was negatively correlated with vulnerable narcissism, the borderline traits “affective instability”, “identity problems”, and the global borderline score. The findings for nAchievement are consistent with earlier reports that suggest that this motive may be a resilience factor[51] associated with good mental health[52], positive identity development[53] and positive social relations[54]. We suggest that in this context high scores on “cold heartedness” should be interpreted non-pathologically as equanimity. Findings for nAffiliation fit earlier observations of individuals with high scores on this disposition being more prosocial and having higher emotional well-being than others[55][56]. The positive correlation between activity inhibition and the AQ score, representing the largest correlation we obtained with PSE-based measures, is puzzling in light of the social and contextual sensitivity attributed to individuals with high activity inhibition in previous research[57] and needs to be replicated before it should be interpreted.

Limitations

This study has some important limitations, including the small sample size, the use of university students as participants, and the fact that couple dominance was not assessed in couples. Further studies in larger and more heterogeneous samples are needed to replicate and confirm the results we obtained in the present research. Future studies may also benefit from using a more predictive approach, instead of a correlational one, to test for the causal effects of personality traits and power motivation, both explicit and implicit, on couple dominance.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the present study presents a novel approach to the issue of interpersonal power (here explored in the context of couple dominance) in relation to personality and motivation, and some intriguing preliminary findings. Personality traits and power motivation appear to influence whether an individual becomes dominant or subordinate in a romantic relationship both independently and jointly. Traits such as extraversion, conscientiousness, and honesty-humility had weak associations with couple dominance and/or explicit or implicit power motivation. Autistic-like traits were associated with being subordinate, while some aspects of narcissistic, psychopathic, and/or borderline traits were associated with being dominant and having high explicit power motivation. The relationship between explicit and implicit power motives, and how they interact with personality and social dynamics need to be further investigated. Our findings have implications for research on romantic relationships, as the dominance dynamics within a couple and the personality profile of the dominant and the subordinate individual may influence relationship stability, quality, and satisfaction[43][58]. Our results also have implications for the understanding of interpersonally aggressive traits such as narcissism, psychopathy, and borderline, as they suggest that these traits can be functionally related to power dynamics in inter-personal relationships and facilitate the expression of self-assertiveness and the control and manipulation of others.

Table 1. Sex differences in the study variables

Click here to download Table 1

Table 2. Partial correlations controlling for age and sex

Click here to download Table 2

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the late Scott O. Lilienfeld for helpful discussions of conceptual and methodological aspects of this research.

Conflict of Interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors have no funding sources to report.

Author Contributions

JIB-L: Data Analysis, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. CS: Data collection, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. OCS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Data Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. RL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. DM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing.

References

- ↑ Maestripieri, D. (2012). Games Primates Play. An Undercover Investigation of the Evolution and Economics of Human Relationships. New York: Basic Books.

- ↑ Bentley, C. G., Galliher, R. V., & Ferguson, T. J. (2007). Associations among aspects of interpersonal power and relationship functioning in adolescent romantic couples. Sex Roles, 57(7-8), 483-495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9280-7

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dunbar, N. E., & Burgoon, J. K. (2005). Perceptions of power and interactional dominance in interpersonal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(2), 207-233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505050944

- ↑ Felmlee, D. H. (1994). Who's on top? Power in romantic relationships. Sex Roles, 31(5), 275-295. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01544589

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Maestripieri, D., Klimczuk, A. C., Seneczko, M., Traficonte, D. M., & Wilson, M. C. (2013). Relationship status and relationship instability, but not dominance, predict individual differences in baseline cortisol levels. PLoS One, 8(12), e84003. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084003

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Simpson, J. A., Farrell, A. K., Oriña, M. M., & Rothman, A. J. (2015). Power and social influence in relationships. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. A. Simpson, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 393–420). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14344-015

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Ponzi, D., Klimczuk, A. C., Traficonte, D. M., & Maestripieri, D. (2015). Perceived dominance in young heterosexual couples in relation to sex, context, and frequency of arguing. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9(1), 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000031

- ↑ Ostrov, J. M., & Collins, W. A. (2007). Social dominance in romantic relationships: A prospective longitudinal study of non‐verbal processes. Social Development, 16(3), 580-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00397.x

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 McClelland, D. C., Koestner, R., & Weinberger, J. (1989). How do self-attributed and implicit motives differ? Psychological Review, 96(4), 690-702. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.690

- ↑ Schultheiss, O. C., & Köllner, M. G. (2021). Implicit motives. In O. P. John & R. W. Robins (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (4 ed., pp. 385-410). New York: Guilford.

- ↑ Lukaszewski, A. W., & von Rueden, C. R. (2015). The extraversion continuum in evolutionary perspective: a review of recent theory and evidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 186-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.005

- ↑ Del Giudice, M., Angeleri, R., Brizio, A., & Elena, M. R. (2010). The evolution of autistic-like and schizotypal traits: A sexual selection hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 1, 41. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00041

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Ogunfowora, B., Bourdage, J. S., & Shin, K. H. (2010). The personality bases of socio-political attitudes: The role of Honesty–Humility and Openness to Experience. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 115-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.08.007

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 de Montigny-Malenfant, B., Santerre, M. È., Bouchard, S., Sabourin, S., Lazaridès, A., & Bélanger, C. (2013). Couples’ negative interaction behaviors and borderline personality disorder. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 41(3), 259-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2012.688006

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Kranefeld, I. (2023). Psychopathy in positions of power: The moderating role of position power in the relation between psychopathic meanness and leadership outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 200, 111916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111916

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Vrabel, J. K., Zeigler-Hill, V., Lehtman, M., & Hernandez, K. (2020). Narcissism and perceived power in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(1), 124-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519858685

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Zeigler-Hill, V., & Marcus, D. K., (eds.) (2016). The Dark Side of Personality: Science and practice in social, personality, and clinical psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lilienfeld, S. O., Latzman, R. D., Watts, A. L., Smith, S. F. & Dutton, K. (2014). Correlates of psychopathic personality traits in everyday life: results from a large community survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 740. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00740

- ↑ Lilienfeld, S. O., Waldman, I. D., Landfield, K., Watts, A. L., Rubenzer, S., & Faschingbauer, T. R. (2012). Fearless dominance and the US Presidency: implications of psychopathic personality traits for successful and unsuccessful political leadership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 489-505. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029392

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Persson, B. N., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2019). Social status as one key indicator of successful psychopathy: an initial empirical investigation. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 209-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.020

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Jonason, P. K., & Ferrell, J. D. (2016). Looking under the hood: The psychogenic motivational foundations of the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 324-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.039

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Emmons, R. A. (1989). Exploring the relations between motives and traits: The case of narcissism. In D. M. Buss & N. Cantor (Eds.), Personality psychology: Recent trends and emerging directions (pp. 32-44). New York: Springer.

- ↑ Schultheiss, O. C. (2018). Implicit motives and hemispheric processing differences are critical for understanding personality disorders: A commentary on Hopwood. European Journal of Personality, 32, 580-582.

- ↑ Borráz-León, J. I., Rantala, M. J., & Cerda-Molina, A. L. (2019). Digit ratio (2D:4D) and facial fluctuating asymmetry as predictors of the dark triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 50-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.08.008

- ↑ Stewart, A. J., & Rubin, Z. (1976). The power motive in the dating couple. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 305-309. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.2.305

- ↑ Marvel-Coen, J., Nickels, N., & Maestripieri, D. (2018). The relationship between morningness-eveningness, psychosocial variables, and cortisol reactivity to stress from a life history perspective. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 12, 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000113

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Murphy, B. A., Casto, K. V., Watts, A. L., Costello, T. H., Jolink, T. A., Verona, E., & Algoe, S. B. (2022). “Feeling Powerful” versus “Desiring Power”: A pervasive and problematic conflation in personality assessment? Journal of Research in Personality, 101, 104305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104305

- ↑ Langens, T. A. (2010). Activity inhibition. In O. C. Schultheiss & J. C. Brunstein (Eds.), Implicit Motives (pp. 89-115). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Spangler, W. D., & House, R. J. (1991). Presidential effectiveness and the leadership motive profile. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 439-455. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.439

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Schultheiss, O. C., & Pang, J. S. (2007). Measuring implicit motives. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology (pp. 322-344). New York: Guilford.

- ↑ Winter, D. G. (1994). Manual for scoring motive imagery in running text (4 ed.). Unpublished manuscript.

- ↑ Schönbrodt, F. D., Hagemeyer, B., Brandstatter, V., Czikmantori, T., Gropel, P., Hennecke, M., Israel, L. S. F., Janson, K. T., Kemper, N., Kollner, M. G., Kopp, P. M., Mojzisch, A., Muller-Hotop, R., Prufer, J., Quirin, M., Scheidemann, B., Schiestel, L., Schulz-Hardt, S., Sust, L. N. N., Zygar-Hoffmann, C., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2021). Measuring implicit motives with the Picture Story Exercise (PSE): Databases of expert-coded German stories, pictures, and updated picture norms. Journal of Personality Assessment, 103(3), 392-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2020.1726936

- ↑ Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2009). The HEXACO–60: a short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91, 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890902935878

- ↑ Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5-17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653411471

- ↑ Jackson, K., M., & Trull, T. J. (2001). The factor structure of the Personality Assessment Inventory-Borderline Features (PAI-BOR) Scale in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Personality Disorders, 15, 536-545. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.15.6.536.19187

- ↑ Nikolova, N. (2009). Comprehensive assessment of psychopathic personality disorder-institutional rating scale (CAPP-IRS)–validation. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Simon Fraser University, Canada.

- ↑ Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

- ↑ Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray's Narcissism Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(4), 588-599. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204

- ↑ Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

- ↑ Wei, T., & Simko, V. (2021). R package ‘corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix (Version 0.92). Available from https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot.

- ↑ R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Carroll, L. (1987). A study of narcissism, affiliation, intimacy, and power motives among students in business administration. Psychological Reports, 61, 355-358. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1987.61.2.355

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Lindová, J., Průšová, D., & Klapilová, K. (2020). Power distribution and relationship quality in long-term heterosexual couples. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(6), 528-541. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1761493

- ↑ Engeser, S., & Langens, T. (2010). Mapping explicit social motives of achievement, power, and affiliation onto the five‐factor model of personality. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(4), 309-318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00773.x

- ↑ Schattke, K., & Marion-Jetten, A. S. (2021). Distinguishing the explicit power motives: Relations with dark personality traits, work behavior, and leadership styles. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 230(4), 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000481

- ↑ Brazil, K., Dias, C. J., & Forth, A. E. (2021). Successful and selective exploitation in psychopathy: convincing others and gaining trust. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, 110394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110394

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Blanchard, A., E., Dunn, T. J., & Sumich, A. (2021). Borderline personality traits in attractive women and wealthy low attractive men are relatively favored by the opposite sex. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 109964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109964

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Brune, M., Ghiassi, V., & Ribbert, H. (2010). Does borderline personality disorder reflect the pathological extreme of an adaptive reproductive strategy? Insights and hypotheses from evolutionary life-history theory. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 7, 3-9.

- ↑ Köllner, M. G., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2014). Meta-analytic evidence of low convergence between implicit and explicit measures of the needs for achievement, affiliation, and power. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00826

- ↑ Stead, L., Brewer, G., Gardner, K., & Khan, R. (2022). Sexual coercion perpetration and victimization in females: The influence of borderline and histrionic personality traits, rejection sensitivity, and love styles. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 28(1), 15-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2021.1909156

- ↑ Schultheiss, O. C., & Brunstein, J. C. (2005). An implicit motive perspective on competence. In A. J. Elliot & C. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 31-51). New York: Guilford.

- ↑ Neumann, M.-L., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2015). Implicit motives, explicit motives, and critical life events in clinical depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39, 89-99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9642-8

- ↑ Orlofsky, J. L. (1978). Identity formation, nAchievement, and fear of success in college men and women. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 7(1), 49-62. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01538686

- ↑ Groesbeck, B. L. (1958). Toward description of personality in terms of configuration of motives. In J. W. Atkinson (Ed.), Motives in fantasy, action, and society: A method of assessment and study (pp. 383-399). Van Nostrand.

- ↑ Hofer, J., & Busch, H. (2011). Satisfying one's needs for competence and relatedness: consequent domain-specific well-being depends on strength of implicit motives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(9), 1147-1158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211408329

- ↑ Rawolle, M., Schultheiss, O. C., Strasser, A., & Kehr, H. M. (2017). The motivating power of visionary images: Effects on motivation, affect, and behavior. Journal of Personality, 85(6), 769-781. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12285

- ↑ Schultheiss, O. C., Riebel, K., & Jones, N. M. (2009). Activity inhibition: A predictor of lateralized brain function during stress? Neuropsychology, 23, 392-404. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014591

- ↑ Kardum, I., Hudek-Knezevic, J., Mehic, N., & Pilek, M. (2018). The effects of similarity in the dark triad traits on the relationship quality in dating couples. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 38-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.04.020